Mental illness: the invisible plague?

At a time in which mental health in becoming an increasing issue, and one which people are more aware of than ever before, Abs Epstein discusses why it isn't taken seriously and what it's really like to suffer from certain disorders.

Why is mental health still not taken seriously?

Mental health is a real issue – it just isn’t talked about enough.

Earlier this year the Telegraph newspaper conducted a poll of over 1000 employers’ opinions on reasons serious enough to be absent from work.

While over 40 percent considered the flu to be an acceptable reason to be absent from work, less than a quarter believed that anxiety was a plausible enough reason.

This kind of opinion about mental health is still very widespread – many people view mental illnesses such as depression as cheap excuses to get out of doing things and be lazy, and stress disorders such as anxiety as simply ‘nerves’.

However, a worrying number of people are unaware of just how serious an issue mental illness is.

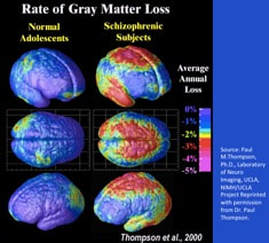

The University of California carried out a study using neurotypical (without mental illnesses or disorders) adolescent subjects and schizophrenic counterparts, and scanning their brains – they found that there are key physical differences in the makeup of the brain between these two groups, thus reflected through their mental disorders.

As well as this, it has been proven that mental illnesses can be due to a defect where the brain is unable to produce sufficient or consistent levels of chemicals like dopamine or serotonin, which stabilise mood, and positive emotions and energy.

The fact that there is solid physical evidence to prove that mental illness can be caused by physical factors and has physical effects shows that there is no excuse for people to dismiss mental health problems as genuine issues.

It has also been proven that, especially in later life, suffering with stress for long periods of time can lead to serious health implications such as cardiovascular disease, heart attacks, stroke, permanent hair loss and gastrointestinal problems such as gastroesophageal reflux disease.

By refusing to accept mental health issues as plausible explanations for job absences, employers are likely making the problem their employees are faced with worse, making them even less likely to be in a fit state to perform tasks at work, and potentially even leading to physical health problems which would necessitate even more time off of work. However, the fact that so many people are not aware of the physical factors affecting mental health and physical outcomes from mental illnesses proves that there is an issue somewhere else: communication.

If mental health was an open and freely discussed topic, everyone would be clear on how serious an issue it is. Currently, however, this is not the case. Mental illness is often quite a taboo topic, with many sufferers feeling unable to open up about their problems and get help, and thus many non-sufferers not being aware of how debilitating mental illness can be.

In all aspects of society, improvement is needed. Families need to talk to their children openly from a young age about not just physical illnesses like sick bugs and headaches, but mental illnesses, which they are just as susceptible to. In the education system, there should be teaching about mental health from primary school in PSHE and general open discussion, just like with physical illness, and advice on how to cope or where to go if they are struggling. Fifty percent of mental health problems are established by the age of 14, so it is apparent that one significant place to tackle the problem is with younger children.

If people receive knowledge, education and support on mental health, it will be much easier for them to access help when they are struggling, instead of being mocked or shunned by people like employers, who currently largely have an outdated, inaccurate view of mental health and its credibility as a real issue.

Communication is the key to combat mental illness.

Earlier this year the Telegraph newspaper conducted a poll of over 1000 employers’ opinions on reasons serious enough to be absent from work.

While over 40 percent considered the flu to be an acceptable reason to be absent from work, less than a quarter believed that anxiety was a plausible enough reason.

This kind of opinion about mental health is still very widespread – many people view mental illnesses such as depression as cheap excuses to get out of doing things and be lazy, and stress disorders such as anxiety as simply ‘nerves’.

However, a worrying number of people are unaware of just how serious an issue mental illness is.

The University of California carried out a study using neurotypical (without mental illnesses or disorders) adolescent subjects and schizophrenic counterparts, and scanning their brains – they found that there are key physical differences in the makeup of the brain between these two groups, thus reflected through their mental disorders.

As well as this, it has been proven that mental illnesses can be due to a defect where the brain is unable to produce sufficient or consistent levels of chemicals like dopamine or serotonin, which stabilise mood, and positive emotions and energy.

The fact that there is solid physical evidence to prove that mental illness can be caused by physical factors and has physical effects shows that there is no excuse for people to dismiss mental health problems as genuine issues.

It has also been proven that, especially in later life, suffering with stress for long periods of time can lead to serious health implications such as cardiovascular disease, heart attacks, stroke, permanent hair loss and gastrointestinal problems such as gastroesophageal reflux disease.

By refusing to accept mental health issues as plausible explanations for job absences, employers are likely making the problem their employees are faced with worse, making them even less likely to be in a fit state to perform tasks at work, and potentially even leading to physical health problems which would necessitate even more time off of work. However, the fact that so many people are not aware of the physical factors affecting mental health and physical outcomes from mental illnesses proves that there is an issue somewhere else: communication.

If mental health was an open and freely discussed topic, everyone would be clear on how serious an issue it is. Currently, however, this is not the case. Mental illness is often quite a taboo topic, with many sufferers feeling unable to open up about their problems and get help, and thus many non-sufferers not being aware of how debilitating mental illness can be.

In all aspects of society, improvement is needed. Families need to talk to their children openly from a young age about not just physical illnesses like sick bugs and headaches, but mental illnesses, which they are just as susceptible to. In the education system, there should be teaching about mental health from primary school in PSHE and general open discussion, just like with physical illness, and advice on how to cope or where to go if they are struggling. Fifty percent of mental health problems are established by the age of 14, so it is apparent that one significant place to tackle the problem is with younger children.

If people receive knowledge, education and support on mental health, it will be much easier for them to access help when they are struggling, instead of being mocked or shunned by people like employers, who currently largely have an outdated, inaccurate view of mental health and its credibility as a real issue.

Communication is the key to combat mental illness.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Organised Clean Disorder? Not so much

Take a look at these images.

Take a look at these images.

Nice, aren’t they? You might even say they ‘satisfy your OCD’. If these pictures made you pleased, there’s a chance you enjoy organisation – your friends or family might have referred to you before as ‘so OCD’.

However, it’s likely that you don’t have OCD at all.

OCD, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, is a debilitating mental illness that I have the misfortune of suffering.

The World Health Organisation once ranked OCD in the top ten of most disabling illnesses of any kind, due to its extremely stressful nature and diminished quality of life for those who suffer with it severely.

I, for one, am not a particularly organised individual for the most part – for example, this is how I keep my makeup most of the time:

However, it’s likely that you don’t have OCD at all.

OCD, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, is a debilitating mental illness that I have the misfortune of suffering.

The World Health Organisation once ranked OCD in the top ten of most disabling illnesses of any kind, due to its extremely stressful nature and diminished quality of life for those who suffer with it severely.

I, for one, am not a particularly organised individual for the most part – for example, this is how I keep my makeup most of the time:

Therefore, it’s clear that obsessive-compulsive disorder is not synonymous with organisation.

If an out-of-line street tile gets you a little annoyed, you probably don’t have OCD.

If said out-of-line street tile brings you to a point of extreme anxiety and causes you to lose sleep, have intrusive thoughts or break down, you may be suffering with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

This is not to say that OCD simply means that disorganisation deeply bothers you instead of slightly; there are a multitude of different forms of the disorder that an individual can suffer with – and it is possible to suffer with more than one.

To begin with, let’s break down what it really means.

The ‘obsession’ in obsessive-compulsive disorder refers to unwanted, unpleasant and possibly intrusive or disturbing thoughts that enter your mind unwillingly and seem near-impossible to get rid of, causing feelings like anxiety, fear or disgust.

The ‘compulsion’ refers to a repetitive behavior, habit or mental act that individuals with OCD feel they need to perform in order to make the obsessive thought go away, bringing temporary relief, but not permanent.

For example, an individual who has an obsessive thought that they may catch a fatal disease and die may repeatedly wash their hands to the point of bleeding, or look up symptoms on the Internet over and over in order to feel relief from their fear.

Anyone can develop OCD at any point in life, but it is most commonly developed during puberty and early adulthood, which is likely due to the stress of growing older, and becoming more independent and more in control of your own life, which some find a hard prospect to cope with.

Events can also trigger a development of the disorder, such as being bullied and trying to cope with the resulting emotional damage and fear that results from that, or falling victim to something like a burglary – many people develop OCD after being robbed, as they are terrified that it will happen again, so spend minutes or hours repeatedly checking the locks on their doors and windows before leaving the house.

Contrary to popular belief, obsessive-compulsive disorder is not at all uncommon.

According to the charity OCD-UK, over 1 in 100 people in the UK are suffering from OCD, and this statistic only counts for severe cases – there are many more mild cases of OCD suffered with in this country. It is estimated that almost one million people in this country are currently struggling with it.

I struggle with a type of obsessive compulsive disorder called dermatillomania, which refers to the urge to pick off skin in order to relieve intrusive, unwanted thoughts or anxiety.

While some days are great, others are certainly not-so-great (to put it lightly). However, I am still completely able to function and enjoy things, and I have learned techniques from getting help to try and resist urges – I have had it for years, and am completely used to it.

However, without access to proper help, OCD sadly ruins some people’s lives completely, and leaves them unable to carry out the simplest of tasks.

Therefore, I urge you to stop using the term OCD when referring to aesthetically pleasing or satisfying images, or showing off your highly organised, multi-compartment pencil case.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder ruins lives; that colour-coded t-shirt drawer you're so proud of bears no similarity to what sufferers have to go through.

Abs Epstein, Year 12

If an out-of-line street tile gets you a little annoyed, you probably don’t have OCD.

If said out-of-line street tile brings you to a point of extreme anxiety and causes you to lose sleep, have intrusive thoughts or break down, you may be suffering with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

This is not to say that OCD simply means that disorganisation deeply bothers you instead of slightly; there are a multitude of different forms of the disorder that an individual can suffer with – and it is possible to suffer with more than one.

To begin with, let’s break down what it really means.

The ‘obsession’ in obsessive-compulsive disorder refers to unwanted, unpleasant and possibly intrusive or disturbing thoughts that enter your mind unwillingly and seem near-impossible to get rid of, causing feelings like anxiety, fear or disgust.

The ‘compulsion’ refers to a repetitive behavior, habit or mental act that individuals with OCD feel they need to perform in order to make the obsessive thought go away, bringing temporary relief, but not permanent.

For example, an individual who has an obsessive thought that they may catch a fatal disease and die may repeatedly wash their hands to the point of bleeding, or look up symptoms on the Internet over and over in order to feel relief from their fear.

Anyone can develop OCD at any point in life, but it is most commonly developed during puberty and early adulthood, which is likely due to the stress of growing older, and becoming more independent and more in control of your own life, which some find a hard prospect to cope with.

Events can also trigger a development of the disorder, such as being bullied and trying to cope with the resulting emotional damage and fear that results from that, or falling victim to something like a burglary – many people develop OCD after being robbed, as they are terrified that it will happen again, so spend minutes or hours repeatedly checking the locks on their doors and windows before leaving the house.

Contrary to popular belief, obsessive-compulsive disorder is not at all uncommon.

According to the charity OCD-UK, over 1 in 100 people in the UK are suffering from OCD, and this statistic only counts for severe cases – there are many more mild cases of OCD suffered with in this country. It is estimated that almost one million people in this country are currently struggling with it.

I struggle with a type of obsessive compulsive disorder called dermatillomania, which refers to the urge to pick off skin in order to relieve intrusive, unwanted thoughts or anxiety.

While some days are great, others are certainly not-so-great (to put it lightly). However, I am still completely able to function and enjoy things, and I have learned techniques from getting help to try and resist urges – I have had it for years, and am completely used to it.

However, without access to proper help, OCD sadly ruins some people’s lives completely, and leaves them unable to carry out the simplest of tasks.

Therefore, I urge you to stop using the term OCD when referring to aesthetically pleasing or satisfying images, or showing off your highly organised, multi-compartment pencil case.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder ruins lives; that colour-coded t-shirt drawer you're so proud of bears no similarity to what sufferers have to go through.

Abs Epstein, Year 12